5. Managing Input Data¶

One home run is much better than two doubles.

—Steve Jobs

5.1. Introduction¶

While advances in long-context language models (LCs) [Lee et al., 2024] have expanded the amount of information these LLMs can process, significant challenges remain in managing and effectively utilizing extended data inputs:

LLMs are sensitive to input formatting and structure, requiring careful data preparation to achieve optimal results [He et al., 2024, Liu et al., 2024, Tan et al., 2024].

LLMs operate with knowledge cutoffs, providing potentially outdated information that may not reflect current reality and demonstrate problems with temporal knowledge accuracy [Amayuelas et al., 2024].

LLMs also face “lost-in-the-middle” problems [Wu et al., 2024] and struggle with less common but important information showing a systematic loss of long-tail knowledge [Kotha et al., 2024].

Motivated by these challenges, this chapter explores two key input data components:

Data Pre-Processing: Parsing and chunking documents into a unified format that is suitable and manageable for LLMs to process effectively.

Retrieval Augmentation: Augmenting LLMs with the ability to retrieve relevant, recent, and specialized information.

In data parsing, we will explore some useful open source tools such as Docling and MarkItDown that help transform data into LLM-compatible formats, demonstrating their impact through a case study of structured information extraction from complex PDFs. In a second case study, we will introduce some chunking strategies to help LLMs process long inputs and implement a particular technique called Chunking with Contextual Linking the enables contextually relevant chunk processing.

In retrieval augmentation, we will explore how to enhance LLMs with semantic search capabilities for incorporating external context using RAGs (Retrieval Augmented Generation) using Vector Databases such as ChromaDB. We also discuss whether RAGs will be really needed in the future given the rise of long-context language models.

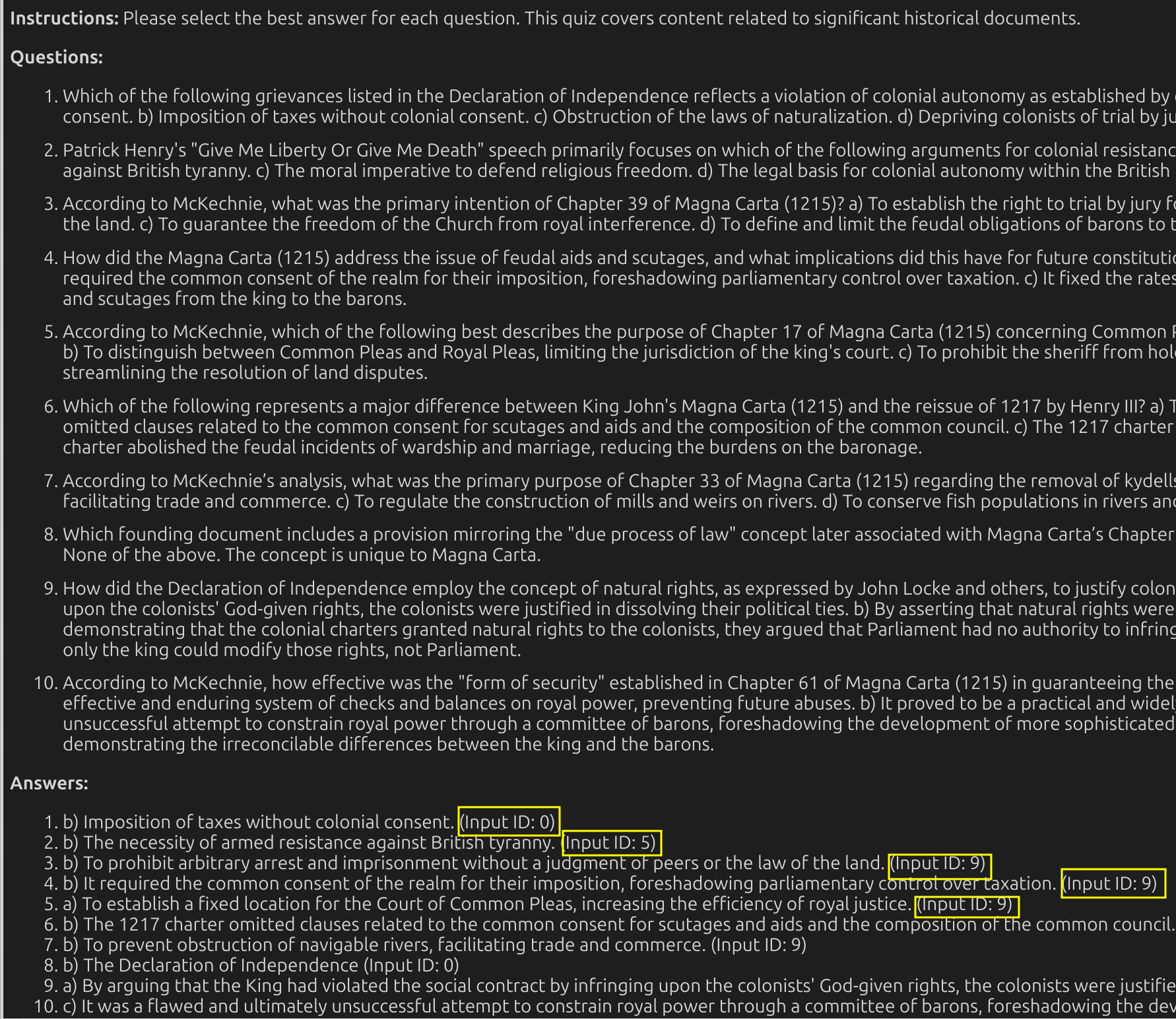

While RAGs are useful for incorporating external context, they are not a silver bullet nor a mandatory component for all LLM applications. In our last case study, we demonstrate how long-context windows can be used to extract insights from a large knowledge base without the need for complex retrieval systems. We build a quiz generator from open books from Project Gutenberg. We will also explore some additional relevant techniques such as prompt caching and response verification through citations using “Corpus-in-Context” (CIC) Prompting [Lee et al., 2024].

By the chapter’s conclusion, readers will possess relevant knowledge of input data management strategies for LLMs and practical expertise in selecting and implementing appropriate approaches and tools for specific use cases.

5.2. Parsing Documents¶

Data parsing and formatting play a critical role in LLMs performance [He et al., 2024, Liu et al., 2024, Tan et al., 2024]. Hence, building robust data ingestion and preprocessing pipelines is essential for any LLM application.

This section explores open source tools that streamline input data processing, in particular for parsing purposes, providing a unified interface for converting diverse data formats into standardized representations that LLMs can effectively process. By abstracting away format-specific complexities, they allow developers to focus on core application logic rather than parsing implementation details while maximizing LLM’s performance.

We will cover open source tools that provide parsing capabilities for a wide range of data formats. And we will show how some of these tools can be used to extract structured information from complex PDFs demonstrating how the quality of the parser can impact LLM’s performance.

5.2.1. MarkItDown¶

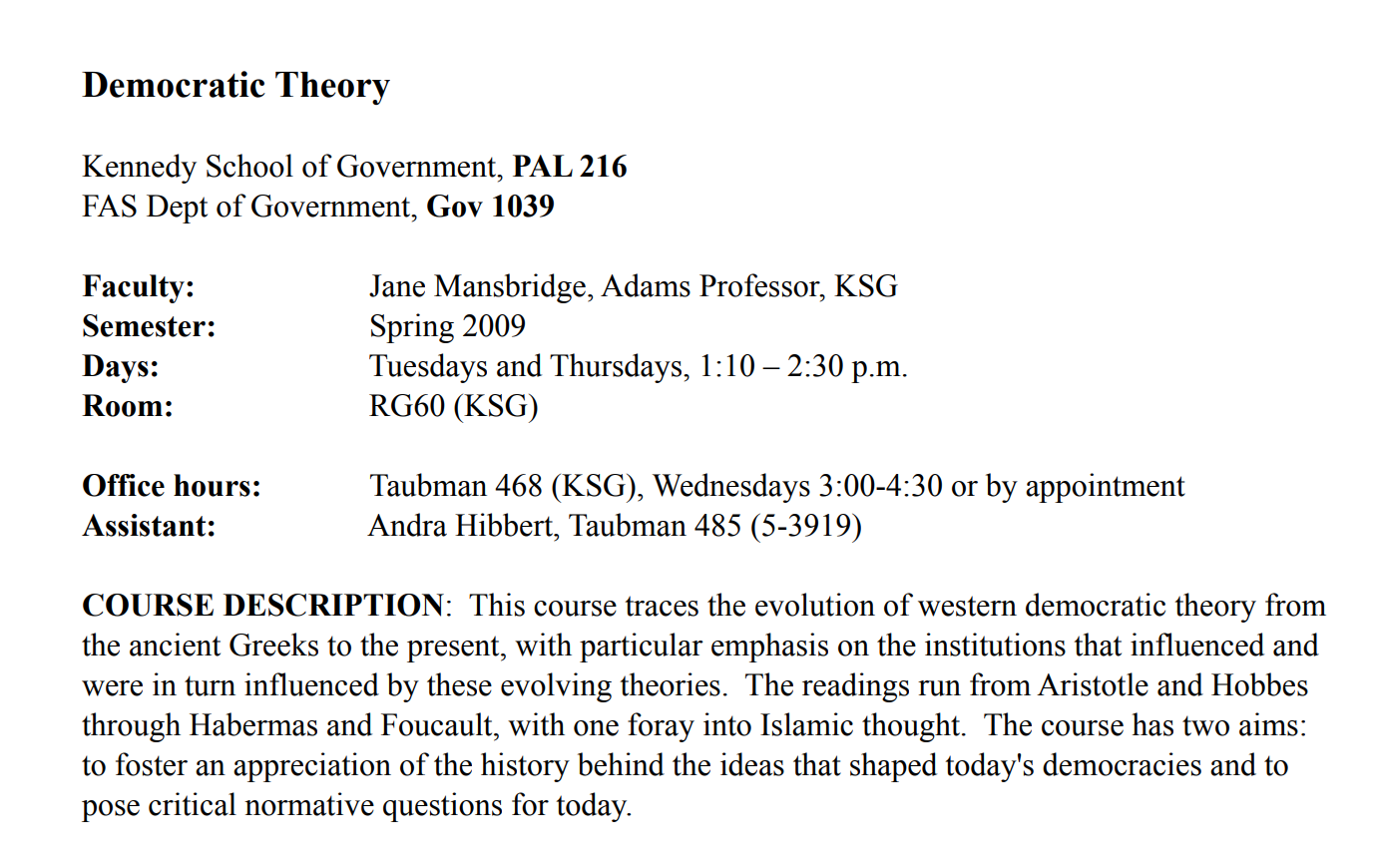

MarkItDown [Microsoft, 2024] is a Python package and CLI tool developed by the Microsoft for converting various file formats to Markdown. It supports a wide range of formats including PDF, PowerPoint, Word, Excel, images (with OCR and EXIF metadata), audio (with transcription), HTML, and other text-based formats making it a useful tool for document indexing and LLM-based applications.

Key features:

Simple command-line and Python API interfaces

Support for multiple file formats

Optional LLM integration for enhanced image descriptions

Batch processing capabilities

Docker support for containerized usage

Sample usage:

from markitdown import MarkItDown

md = MarkItDown()

result = md.convert("test.xlsx")

print(result.text_content)

5.2.2. Docling¶

Docling [IBM Research, 2024] is a Python package developed by IBM Research for parsing and converting documents into various formats. It provides advanced document understanding capabilities with a focus on maintaining document structure and formatting.

Key features:

Support for multiple document formats (PDF, DOCX, PPTX, XLSX, Images, HTML, etc.)

Advanced PDF parsing including layout analysis and table extraction

Unified document representation format

Integration with LlamaIndex and LangChain

OCR support for scanned documents

Simple CLI interface

Sample usage:

from docling.document_converter import DocumentConverter

converter = DocumentConverter()

result = converter.convert("document.pdf")

print(result.document.export_to_markdown())

5.2.3. Structured Data Extraction¶

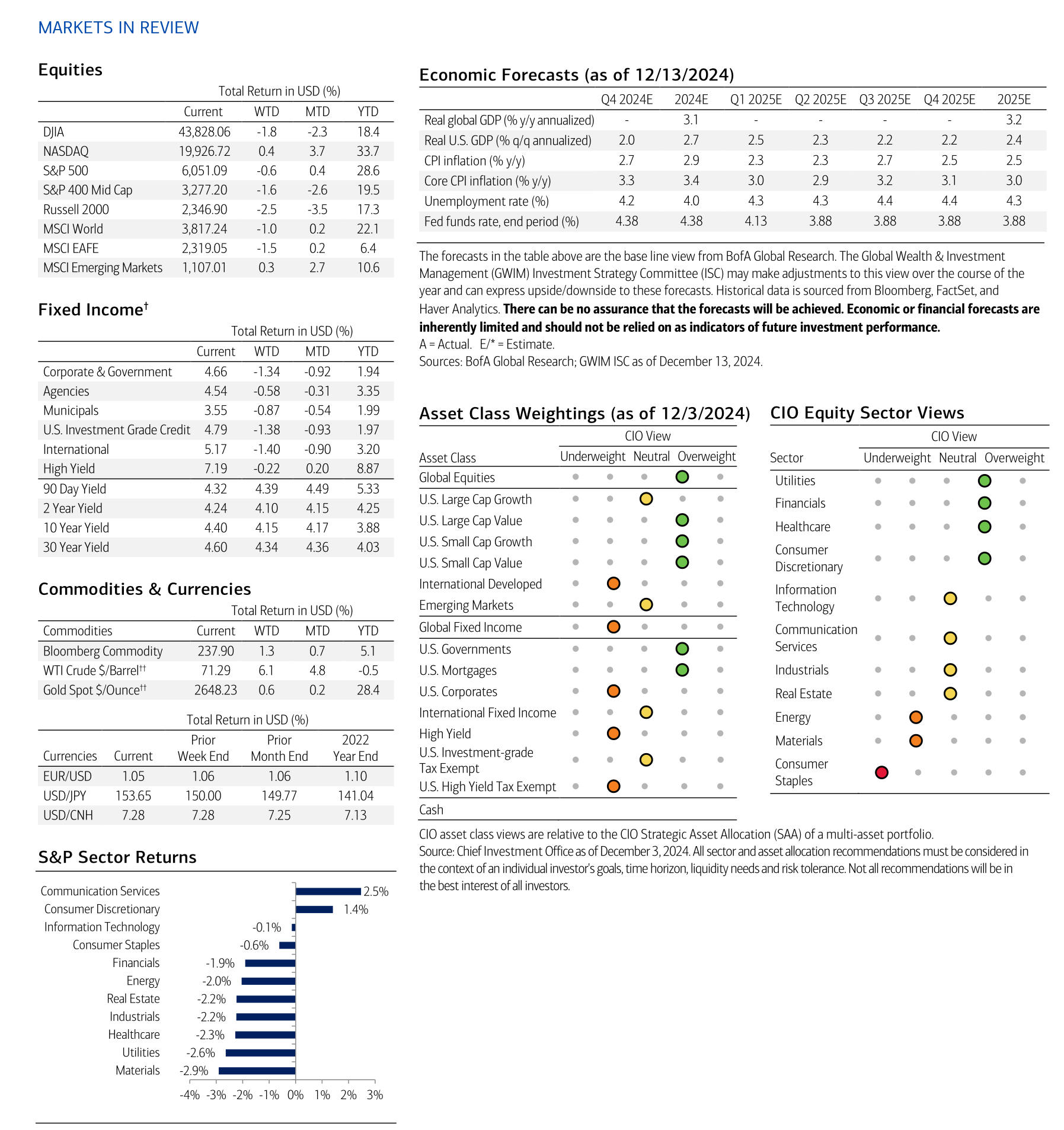

A common use case where document parsing matters is structured data extraction, particularly in the presence of complex formatting and layout. In this case study, we will extract the economic forecasts from Merrill Lynch’s CIO Capital Market Outlook released on December 16, 2024 [Merrill Lynch, 2024]. We will focus on page 7 of this document, which contains several economic variables organized in a mix of tables, text and images (see Fig. 5.1).

Fig. 5.1 Merrill Lynch’s CIO Capital Market Outlook released on December 16, 2024 [Merrill Lynch, 2024]¶

FORECAST_FILE_PATH = "../data/input/forecast.pdf"

First, we will use MarkItDown to extract the text content from the document.

from markitdown import MarkItDown

md = MarkItDown()

result_md = md.convert(FORECAST_FILE_PATH).text_content

Next, we will do the same with Docling.

from docling.document_converter import DocumentConverter

converter = DocumentConverter()

forecast_result_docling = converter.convert(source).document.export_to_markdown()

How similar are the two results? We can use use Levenshtein distance to measure the similarity between the two results. We will also calculate a naive score using the SequenceMatcher from the difflib package, which is a simple measure of similarity between two strings based on the number of matches in the longest common subsequence.

import Levenshtein

def levenshtein_similarity(text1: str, text2: str) -> float:

"""

Calculate normalized Levenshtein distance

Returns value between 0 (completely different) and 1 (identical)

"""

distance = Levenshtein.distance(text1, text2)

max_len = max(len(text1), len(text2))

return 1 - (distance / max_len)

from difflib import SequenceMatcher

def simple_similarity(text1: str, text2: str) -> float:

"""

Calculate similarity ratio using SequenceMatcher

Returns value between 0 (completely different) and 1 (identical)

"""

return SequenceMatcher(None, text1, text2).ratio()

levenshtein_similarity(forecast_result_md, forecast_result_docling)

0.13985705461925346

simple_similarity(forecast_result_md, forecast_result_docling)

0.17779960707269155

It turns out that the two results are quite different, with a similarity score of about 13.98% and 17.77% for Levenshtein and SequenceMatcher, respectively.

Docling’s result is a quite readable markdown displaying key economic variables and their forecasts. Conversely, MarkItDown’s result is a bit messy and hard to read but the information is there just not in a structured format. Does it matter? That’s what we will explore next.

Docling’s result

display(Markdown(forecast_result_docling))

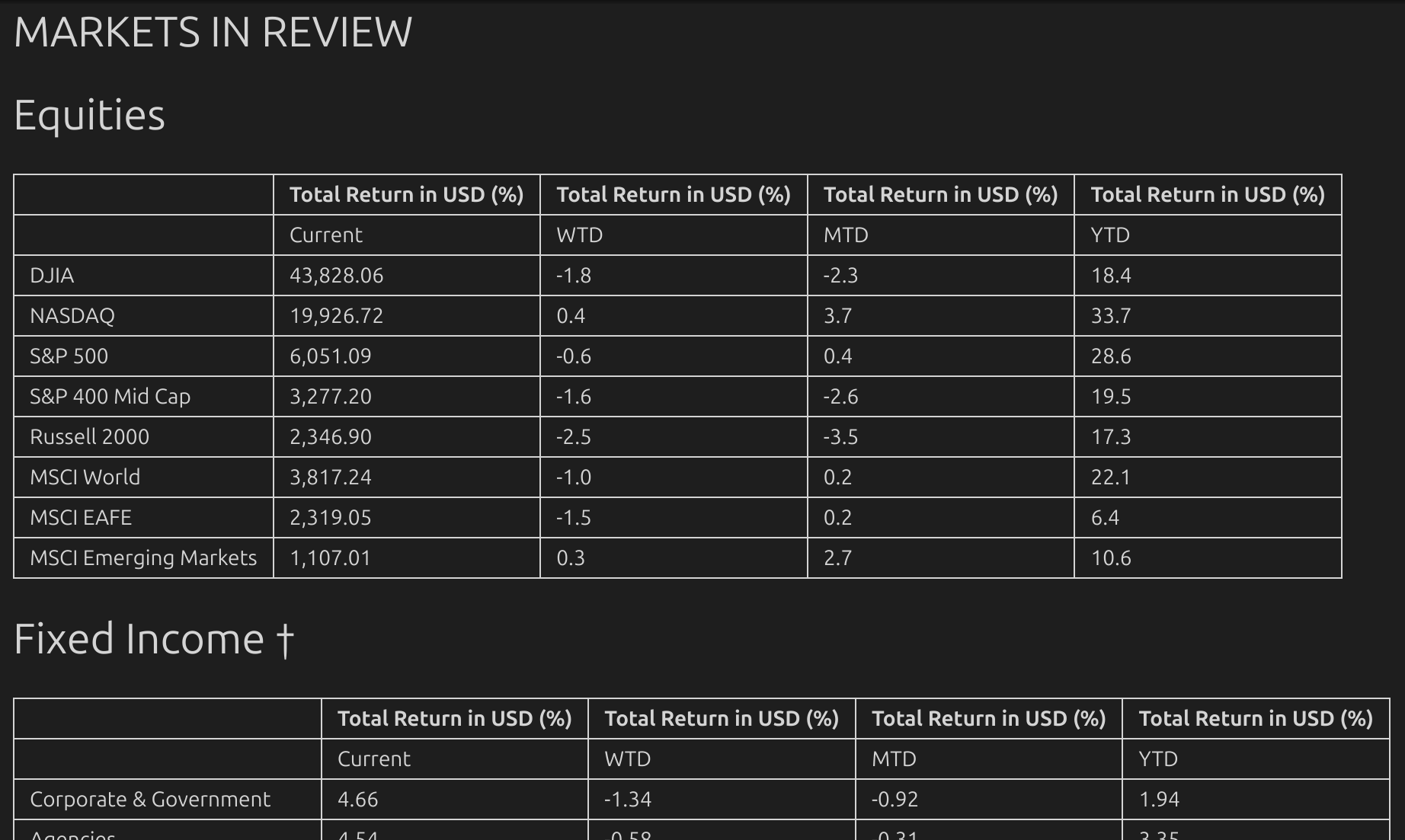

Fig. 5.2 shows part of the parsed result from Docling.

Fig. 5.2 An extract of Docling’s parsed result.¶

MarkItDown’s result

from IPython.display import display, Markdown

display(Markdown(forecast_result_md[:500]))

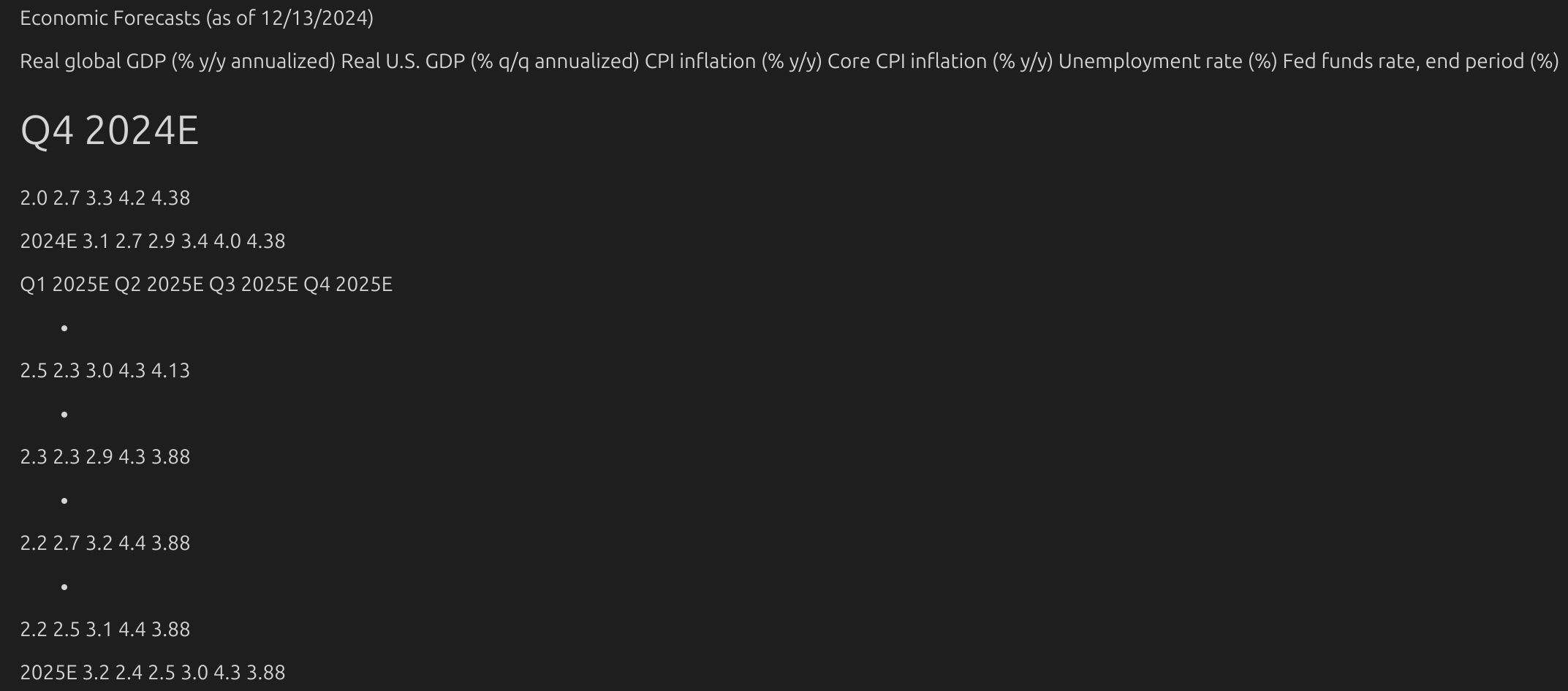

Fig. 5.3 shows part of the parsed result from MarkItDown.

Fig. 5.3 An extract of MarkItDown’s parsed result.¶

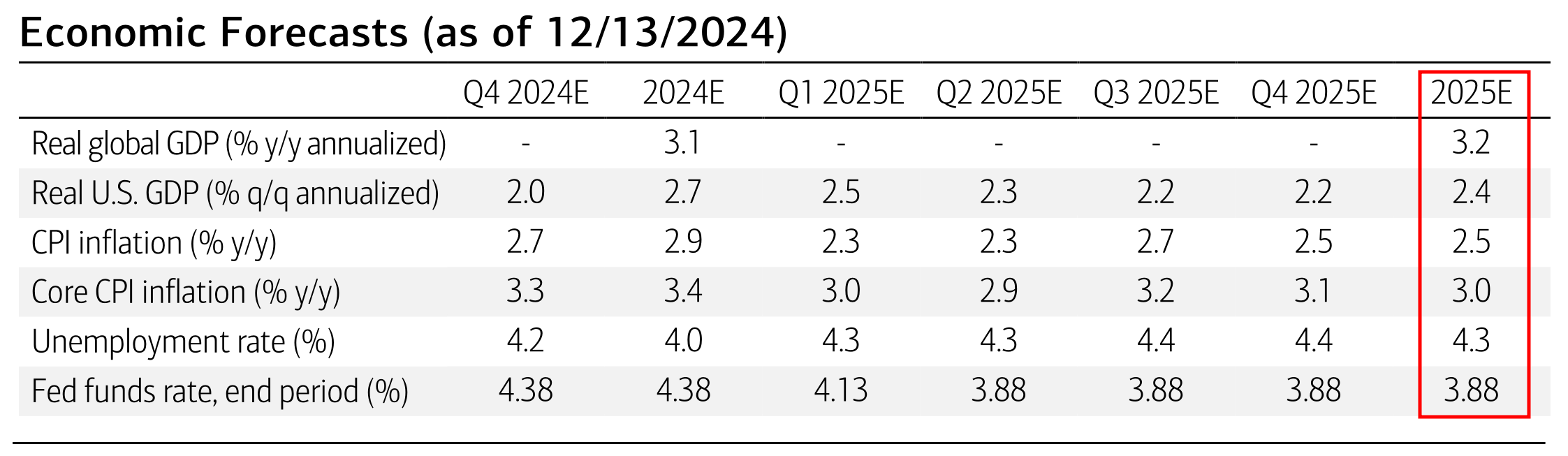

Now, let’s focus on the economic forecasts. In particular, we are interested in extracting the CIO’s 2025E forecasts. This could be a useful predictive indicator for the economy in 2025.

Fig. 5.4 Merrill Lynch’s CIO Economic Forecasts.¶

We will define a Forecast pydantic model to represent an economic forecast composed of a financial_variable and a financial_forecast. We will also define a EconForecast pydantic model to represent the list of economic forecasts we want to extract from the document.

from pydantic import BaseModel

class Forecast(BaseModel):

financial_variable: str

financial_forecast: float

class EconForecast(BaseModel):

forecasts: list[Forecast]

We write a simple function to extract the economic forecasts from the document using an LLM model (with structured output) with the following prompt template, where extract_prompt represents the kind of data the user would like to extract and doc is the input document.

BASE_PROMPT = f"""

ROLE: You are an expert at structured data extraction.

TASK: Extract the following data {extract_prompt} from input DOCUMENT

FORMAT: The output should be a JSON object with 'financial_variable' as key and 'financial_forecast' as value.

"""

prompt = f"{BASE_PROMPT} \n\n DOCUMENT: {doc}"

def extract_from_doc(extract_prompt: str, doc: str, client) -> EconForecast:

"""

Extract data of a financial document using an LLM model.

Args:

doc: The financial document text to analyze

client: The LLM model to use for analysis

extract_prompt: The prompt to use for extraction

Returns:

EconForecasts object containing sentiment analysis results

"""

BASE_PROMPT = f"""

ROLE: You are an expert at structured data extraction.

TASK: Extract the following data {extract_prompt} from input DOCUMENT

FORMAT: The output should be a JSON object with 'financial_variable' as key and 'financial_forecast' as value.

"""

prompt = f"{BASE_PROMPT} \n\n DOCUMENT: {doc}"

completion = client.beta.chat.completions.parse(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

messages=[

{

"role": "system",

"content": prompt

},

{"role": "user", "content": doc}

],

response_format=EconForecast

)

return completion.choices[0].message.parsed

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import os

# Load environment variables from .env file

load_dotenv(override=True)

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

The user then calls the extract_from_doc function simply defining that “Economic Forecasts for 2025E” is the data they would like to extract from the document. We perform the extraction twice, once with MarkItDown and once with Docling.

extract_prompt = "Economic Forecasts for 2025E"

md_financials = extract_from_doc(extract_prompt, forecast_result_md, client)

docling_financials = extract_from_doc(extract_prompt, forecast_result_docling, client)

The response is an EconForecast object containing a list of Forecast objects, as defined in the pydantic model. We can then convert the response to a pandas DataFrame for easier comparison.

md_financials

EconForecast(forecasts=[Forecast(financial_variable='Real global GDP (% y/y annualized)', financial_forecast=3.2), Forecast(financial_variable='Real U.S. GDP (% q/q annualized)', financial_forecast=2.4), Forecast(financial_variable='CPI inflation (% y/y)', financial_forecast=2.5), Forecast(financial_variable='Core CPI inflation (% y/y)', financial_forecast=3.0), Forecast(financial_variable='Unemployment rate (%)', financial_forecast=4.3), Forecast(financial_variable='Fed funds rate, end period (%)', financial_forecast=3.88)])

df_md_forecasts = pd.DataFrame([(f.financial_variable, f.financial_forecast) for f in md_financials.forecasts],

columns=['Variable', 'Forecast'])

df_docling_forecasts = pd.DataFrame([(f.financial_variable, f.financial_forecast) for f in docling_financials.forecasts],

columns=['Variable', 'Forecast'])

df_md_forecasts

| Variable | Forecast | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Real global GDP (% y/y annualized) | 3.20 |

| 1 | Real U.S. GDP (% q/q annualized) | 2.40 |

| 2 | CPI inflation (% y/y) | 2.50 |

| 3 | Core CPI inflation (% y/y) | 3.00 |

| 4 | Unemployment rate (%) | 4.30 |

| 5 | Fed funds rate, end period (%) | 3.88 |

df_docling_forecasts

| Variable | Forecast | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Real global GDP (% y/y annualized) | 3.20 |

| 1 | Real U.S. GDP (% q/q annualized) | 2.40 |

| 2 | CPI inflation (% y/y) | 2.50 |

| 3 | Core CPI inflation (% y/y) | 3.00 |

| 4 | Unemployment rate (%) | 4.30 |

| 5 | Fed funds rate, end period (%) | 3.88 |

The results from MarkItDown and Docling are identical and accurately match the true values from the document. This demonstrates that despite MarkItDown’s output appearing less readable from a human perspective, both approaches enabled the LLM to successfully extract the economic forecast data with equal accuracy, in this particular case.

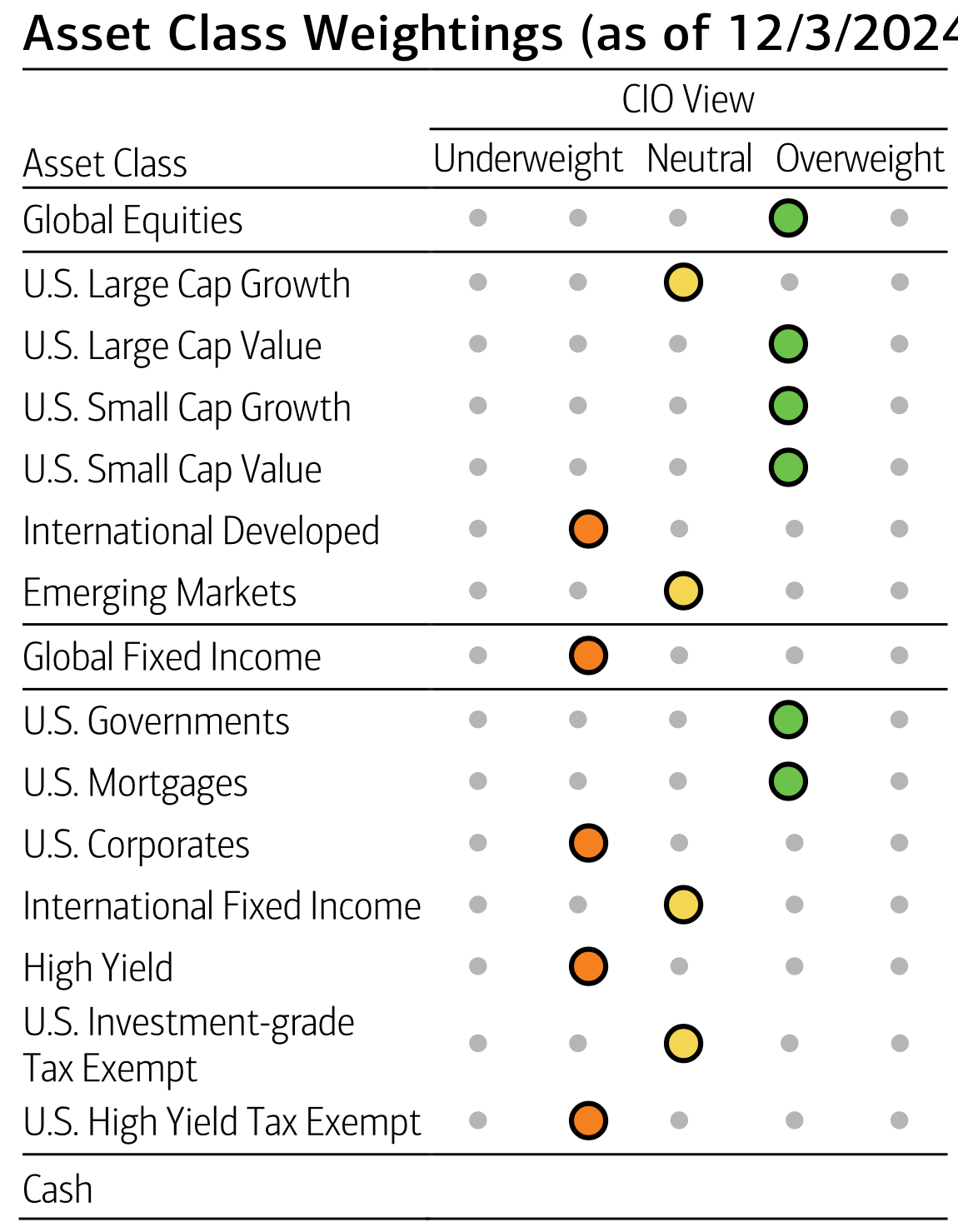

Next, let’s focus on the asset class weightings. We will extract the asset class weightings from the document and compare the results from MarkItDown and Docling. The information is now presented in a quite different structure as we can see in Fig. 5.5. The CIO view information is represented in a spectrum starting with “Underweight”, passing through “Neutral” and reaching “Overweight”. The actual view is marked by some colored dots in the chart. Let’s see if we can extract this relatively more complex information from the document.

Fig. 5.5 Asset Class Weightings¶

The user will simply define the following data to extract: “Asset Class Weightings (as of 12/3/2024) in a scale from -2 to 2”. In that way, we expect that “Underweight” will be mapped to -2, “Neutral” to 0 and “Overweight” to 2 with some values in between.

extract_prompt = "Asset Class Weightings (as of 12/3/2024) in a scale from -2 to 2"

asset_class_docling = extract_from_doc(extract_prompt, forecast_result_docling, client)

asset_class_md = extract_from_doc(extract_prompt, forecast_result_md, client)

df_md = pd.DataFrame([(f.financial_variable, f.financial_forecast) for f in asset_class_md.forecasts],

columns=['Variable', 'Forecast'])

df_docling = pd.DataFrame([(f.financial_variable, f.financial_forecast) for f in asset_class_docling.forecasts],

columns=['Variable', 'Forecast'])

We construct a DataFrame to compare the results from MarkItDown and Docling with an added “true_value” column containing the true values from the document, which we extracted manually from the chart. This enables us to calculate accuracy of the structured data extraction task in case.

# Create DataFrame with specified columns

df_comparison = pd.DataFrame({

'variable': df_docling['Variable'].iloc[:-1],

'markitdown': df_md['Forecast'],

'docling': df_docling['Forecast'].iloc[:-1], # Drop last row

'true_value': [1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, -1.0, 0.0, -1.0, 1.0, 1.0, -1.0, 0.0, -1.0, 0.0, -1.0]

})

display(df_comparison)

| variable | markitdown | docling | true_value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Global Equities | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1 | U.S. Large Cap Growth | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | U.S. Large Cap Value | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 3 | U.S. Small Cap Growth | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 4 | U.S. Small Cap Value | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 5 | International Developed | 1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

| 6 | Emerging Markets | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | Global Fixed Income | -1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

| 8 | U.S. Governments | -1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 9 | U.S. Mortgages | -1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 10 | U.S. Corporates | -1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

| 11 | International Fixed Income | -1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 12 | High Yield | -1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

| 13 | U.S. Investment-grade | -1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 14 | Tax Exempt U.S. High Yield Tax Exempt | -1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

# Calculate accuracy for markitdown and docling

markitdown_accuracy = (df_comparison['markitdown'] == df_comparison['true_value']).mean()

docling_accuracy = (df_comparison['docling'] == df_comparison['true_value']).mean()

print(f"Markitdown accuracy: {markitdown_accuracy:.2%}")

print(f"Docling accuracy: {docling_accuracy:.2%}")

Markitdown accuracy: 53.33%

Docling accuracy: 93.33%

We observe that Docling performs significantly better at 93.33% accuracy missing only one value. MarkItDown achieves 53.33% accuracy struggling with nuanced asset class weightings. In this case, Docling’s structured parsed output did help the LLM to extract the information more accurately compared to MarkItDown’s unstructured output. Hence, in this case, the strategy used to parse the data did impact the LLM’s ability to extract structured information. Having said that, it is important to mention that a more robust analysis would run data extraction on a larger sample data a number of times across repeated runs to estimate confidence intervals since results are non-deterministic.

What if we wanted to systematically extract all tables from the document? We can use Docling to do that by simply accessing the tables attribute of the DocumentConverter object.

By doing that, we observe that Docling successfully extracted the seven tables from the document exporting tables from top down and left to right in order of appearance in the document. Below, we display the first two and the last tables. We can see the first table successfully extracted for Equities forecasts, the second one for Fixed Income forecasts as well as the last table, which contains CIO Equity Sector Views.

import time

from pathlib import Path

import pandas as pd

from docling.document_converter import DocumentConverter

def convert_and_export_tables(file_path: Path) -> list[pd.DataFrame]:

"""

Convert document and export tables to DataFrames.

Args:

file_path: Path to input document

Returns:

List of pandas DataFrames containing the tables

"""

doc_converter = DocumentConverter()

start_time = time.time()

conv_res = doc_converter.convert(file_path)

tables = []

# Export tables

for table in conv_res.document.tables:

table_df: pd.DataFrame = table.export_to_dataframe()

tables.append(table_df)

end_time = time.time() - start_time

print(f"Document converted in {end_time:.2f} seconds.")

return tables

# Convert and export tables

tables = convert_and_export_tables(Path(FORECAST_FILE_PATH))

len(tables)

7

display(tables[0])

| Total Return in USD (%).Current | Total Return in USD (%).WTD | Total Return in USD (%).MTD | Total Return in USD (%).YTD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | DJIA | 43,828.06 | -1.8 | -2.3 | 18.4 |

| 1 | NASDAQ | 19,926.72 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 33.7 |

| 2 | S&P 500 | 6,051.09 | -0.6 | 0.4 | 28.6 |

| 3 | S&P 400 Mid Cap | 3,277.20 | -1.6 | -2.6 | 19.5 |

| 4 | Russell 2000 | 2,346.90 | -2.5 | -3.5 | 17.3 |

| 5 | MSCI World | 3,817.24 | -1.0 | 0.2 | 22.1 |

| 6 | MSCI EAFE | 2,319.05 | -1.5 | 0.2 | 6.4 |

| 7 | MSCI Emerging Markets | 1,107.01 | 0.3 | 2.7 | 10.6 |

display(tables[1])

| Total Return in USD (%).Current | Total Return in USD (%).WTD | Total Return in USD (%).MTD | Total Return in USD (%).YTD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Corporate & Government | 4.66 | -1.34 | -0.92 | 1.94 |

| 1 | Agencies | 4.54 | -0.58 | -0.31 | 3.35 |

| 2 | Municipals | 3.55 | -0.87 | -0.54 | 1.99 |

| 3 | U.S. Investment Grade Credit | 4.79 | -1.38 | -0.93 | 1.97 |

| 4 | International | 5.17 | -1.40 | -0.90 | 3.20 |

| 5 | High Yield | 7.19 | -0.22 | 0.20 | 8.87 |

| 6 | 90 Day Yield | 4.32 | 4.39 | 4.49 | 5.33 |

| 7 | 2 Year Yield | 4.24 | 4.10 | 4.15 | 4.25 |

| 8 | 10 Year Yield | 4.40 | 4.15 | 4.17 | 3.88 |

| 9 | 30 Year Yield | 4.60 | 4.34 | 4.36 | 4.03 |

display(tables[6])

| Sector | CIO View. | CIO View.Underweight | CIO View.Neutral | CIO View. | CIO View.Overweight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Utilities | slight over weight green | | | | |

| 1 | Financials | slight over weight green | | | | |

| 2 | Healthcare | slight over weight green | | | | |

| 3 | Consumer Discretionary | Slight over weight green | | | | |

| 4 | Information Technology | Neutral yellow | | | | |

| 5 | Communication Services | Neutral yellow | | | | |

| 6 | Industrials | Neutral yellow | | | | |

| 7 | Real Estate | Neutral yellow | | | | |

| 8 | Energy | slight underweight orange | | | | |

| 9 | Materials | slight underweight orange | | | | |

| 10 | Consumer Staples | underweight red | | | | |

Coming back to MarkItDown, one interesting feature to explore is the ability to extract information from images by passing an image capable LLM model to its constructor.

md_llm = MarkItDown(llm_client=client, llm_model="gpt-4o-mini")

result = md_llm.convert("../data/input/forecast.png")

Here’s the description we obtain from the image of our input document.

display(Markdown(result.text_content))

Description:

Markets in Review: Economic Forecasts and Asset Class Weightings (as of 12/13/2024)

This detailed market overview presents key performance metrics and economic forecasts as of December 13, 2024.

Equities Overview:

Total Returns: Highlights returns for major indices such as the DJIA (18.4% YTD), NASDAQ (33.7% YTD), and S&P 500 (28.6% YTD), showcasing strong performance across the board.

Forecasts: Economic indicators reveal a projected real global GDP growth of 3.1%, with inflation rates expected to stabilize around 2.2% in 2025. Unemployment rates are anticipated to remain low at 4.4%.

Fixed Income:

Focuses on various segments, including Corporate & Government bonds, which offer an annualized return of 4.66% and indicate shifting trends in interest rates over 2-Year (4.25%) and 10-Year (4.03%) bonds.

Commodities & Currencies:

Commodities such as crude oil and gold show varied performance, with oil increasing by 4.8% and gold prices sitting at $2,648.23 per ounce.

Currency metrics highlight the Euro and USD trends over the past year.

S&P Sector Returns:

A quick reference for sector performance indicates a significant 2.5% return in Communication Services, while other sectors like Consumer Staples and Materials display minor fluctuations.

CIO Asset Class Weightings:

Emphasizes strategic asset allocation recommendations which are crucial for an investor’s portfolio. Underweight positions in U.S. Small Cap Growth and International Developed contrast with overweight positions in certain sectors such as Utilities and Financials, signaling tactical shifts based on ongoing economic assessments.

Note: This summary is sourced from BofA Global Research and aims to provide a comprehensive view of current market conditions and forecasts to assist investors in making informed decisions.

Overall, the description is somewhat accurate but contains a few inaccuracies including:

For the sector weightings, the description states there are “underweight positions in U.S. Small Cap Growth” but looking at the Asset Class Weightings chart, U.S. Small Cap Growth actually shows an overweight position (green circle).

The description mentions “overweight positions in certain sectors such as Utilities and Financials” but looking at the CIO Equity Sector Views, both these sectors show neutral positions, not overweight positions.

For fixed income, the description cites a “10-Year (4.03%)” yield, but the image shows the 30-Year Yield at 4.03%, while the 10-Year Yield is actually 4.40%.

Arguably, the description’s inaccuracies could be a consequence of the underlying LLM model’s inability to process the image.

We have covered MarkitDown and Docling as examples of open source tools that can help developers parse input data into a suitable format to LLMs. Other relevant open source tools worth mentioning include:

Unstructured [Unstructured.io, 2024]: A Python library for unstructured data extraction.

FireCrawl [Mendable AI, 2024]: A Fast and Efficient Web Crawler for LLM Training Data.

LlamaParse [LlamaIndex, 2024]: Llamaindex’s data parsing solution.

The choice of tool depends on the specific requirements of the application and the nature of the input data. This choice should be taken as a critical decision of any data intensive LLM-based application and deserves dedicated research and evidence-based experimentation early-on in the development cycle.

5.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation¶

What happens if we asked ChatGPT who’s the author of the book “Taming LLMs”?

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import os

# Load environment variables from .env file

load_dotenv()

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

model = "gpt-4o-mini"

question = "Who's the Author of the Book Taming LLMs?"

response = client.chat.completions.parse(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

messages=[

{"role": "user", "content": question}

]

)

response.choices[0].message.content

The book "Taming LLMs" is authored by *G. Arulkumaran, H. M. B. P. D. Karthikeyan, and I. A. M. Almasri.* If you need more information about the book or its contents, feel free to ask!

Turns out ChatGPT hallucinates. A quick web search on the before mentioned authors yields no results. In fact, those authors names are made up. And of course the correct answer would have been yours truly, “Tharsis Souza”.

LLMs only have access to the information they have been trained on, which of course has been fixed at a point in time. Hence, LLMs operate with stale data. The problem gets exacerbated by the fact that LLMs are trained to provide an answer even if the answer is unknown by them, hence leading to hallucinations.

One solution to this problem is to use a retrieval system to fetch information from a knowledge base to provide recent and relevant context to user queries using so-called Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) system.

RAG utilizes a retrieval system to fetch external knowledge and augment LLM’s context. It is a useful technique for building LLM applications that require domain-specific information or knowledge-intensive tasks [Lewis et al., 2021]. It has also proved effective in mitigating LLMs hallucinations [Ni et al., 2024, Zhou et al., 2024].

In the above example, a RAG would help with hallucinations by grounding the LLM’s response to information provided in the knowledge base. Additional common use cases of RAG systems include:

Enterprise Knowledge Management: RAG enables organizations to synthesize answers from diverse internal data sources like documents, databases, and communication channels. This creates a unified knowledge interface that can accurately answer questions using the organization’s own data.

Document Processing and Analysis: RAG excels at extracting and analyzing information from complex documents like financial reports, presentations, and spreadsheets. The system can enable LLMs to understand context and relationships across different document types and formats.

Intelligent Customer Support: By combining knowledge bases with conversational abilities, RAG powers chatbots and support systems that can maintain context across chat history, provide accurate responses, and handle complex customer queries while reducing hallucinations.

Domain-Specific Applications: RAG allows LLMs to be equipped with specialized knowledge in fields like medicine, law, or engineering by retrieving information from domain-specific literature, regulations, and technical documentation. This enables accurate responses aligned with professional standards and current best practices.

Code Documentation and Technical Support: RAG can help developers by retrieving relevant code examples, API documentation, and best practices from repositories and documentation, which often suffer updates frequently, enabling more accurate and contextual coding assistance.

If LLMs alone work on stale, general-purpose data with the added challenge of being prone to hallucinations, RAG systems serve as an added capability enabling LLMs to work on recent, domain-specific knowledge increasing the likelihood of LLMs to provide responses that are factual and relevant to user’s queries.

5.3.1. RAG Pipeline¶

RAG architectures vary but they all share the same goal: To retrieve relevant information from a knowledge base to maximize the LLM’s ability to effectively and accurately respond to prompts, particularly when the answer requires out-of-training data.

We will introduce key components of a RAG system one by one leading to a full canonical RAG pipeline at the end that ultimately will be used to answer our original question “Who’s the author of the book Taming LLMs?”, accurately.

The following basic components will be introduced (see Fig. 5.6 for a visual representation):

Vector Database

Embeddings

Indexing

Retrieval System including re-ranking

LLM Augmented Generation via in-context learning

Data extraction, parsing and chunking are also part of a canonical pipeline as we prepare the knowledge base. Those are concepts we explored in detail in Sections Parsing Documents and Case Study I: Content Chunking with Contextual Linking, hence we will be succinct here. We will start by preparing the knowledge base.

Fig. 5.6 Simplified RAG Pipeline¶

5.3.1.1. Preparing the Knowledge Base¶

Every RAG system requires a knowledge base. In our case, the knowledge base is a set of documents that we equip the LLM with to answer our authorship question.

Hence, we will compose our knowledge base by adding the web version of (some of the chapters of) the book “Taming LLMs”, namely:

Introduction

Structured Output

Input (this very chapter)

book_url = "https://www.tamingllms.com/"

chapters = ["markdown/intro.html",

"notebooks/structured_output.html",

"notebooks/input.html"]

chapter_urls = [f"{book_url}/{chapter}" for chapter in chapters]

chapter_ids = [chapter.split("/")[-1].replace(".html", "") for chapter in chapters]

We use Docling to download the chapters from the web and parse them as markdown files.

chapters = [converter.convert(chapter_url).document.export_to_markdown() for chapter_url in chapter_urls]

Now we are ready to store the chapters in a vector database to enable the construction of a retrieval system.

5.3.1.2. Vector Database¶

Vector databases are specialized databases designed to store and retrieve high-dimensional vectors, which are mathematical representations of data like text, images, or audio. These databases are optimized for similarity search operations, making them ideal for embeddings-based retrieval systems.

A typical pipeline involving a vector database includes the following:

Input data is converted into “documents” forming a collection representing our knowledge base

Each document is converted into an embedding which are stored in the vector database

Embeddings are indexed in the vector database for efficient similarity search

The vector database is queried to retrieve the most relevant documents

The retrieved documents are used to answer questions

Vector databases are not a mandatory component of RAG systems. In fact, we can use a simple list of strings to store the chapters (or their chunks) and then use the LLM to answer questions about the document. However, vector databases are useful for RAG applications as they enable:

Fast similarity search for finding relevant context

Efficient storage of document embeddings

Scalable retrieval for large document collections

Flexible querying with metadata filters

In that way, RAG applications can be seen as a retrieval system that uses a vector database to store and retrieve embeddings of documents, which in turn are used to augment LLMs with contextually relevant information as we will see in the next sections.

Here, we will use ChromaDB [ChromaDB, 2024b] as an example of an open source vector database but key features and concepts we cover are applicable to other vector databases, in general.

ChromaDB is a popular open-source vector database that offers:

Efficient storage and retrieval of embeddings

Support for metadata and filtering

Easy integration with Python applications

In-memory and persistent storage options

Support for multiple distance metrics

Other notable vector databases include Weaviate, FAISS, and Milvus.

In ChromaDB, we can create a vector database client as follows.

import chromadb

chroma_client = chromadb.Client()

This will create a vector database in memory. We can also create a persistent vector database by specifying a path to a directory or alternatively by using a cloud-based vector database service like AWS, Azure or GCP. We will use a vector database in memory for this example.

Next, we create a collection to store the embeddings of the chapters. And add our chapters as documents to the collection as follows.

collection = chroma_client.create_collection(name="taming_llms")

collection.add(

documents=chapters,

ids=chapter_ids

)

We are ready to query the collection. We write a simple function that takes the collection, input query and number of retrieved results as argument and returns the retrieved documents.

def query_collection(collection, query_text, n_results=3):

results = collection.query(

query_texts=[query_text],

n_results=n_results

)

return results

We write a simple query, enquiring the purpose of the book.

q = "What is the purpose of this book?"

res = query_collection(collection, q)

res.get("ids")

print([['intro', 'input', 'structured_output']])

As response, we obtain an object that contains several attributes including:

documents: The actual documents retrieved from the collection, i.e. the chaptersids: The ids of the documents retrieved from the collectiondistances: The distances of the documents to the query vector

We can see that the chapters “Introduction”, “Input” and “Structured Output” are retrieved from the collection ordered by their distance to the query vector, in increasing order.

We observe that the Introduction chapter is the most relevant one as it ranks first, followed by the Input and Structured Output chapters. Indeed, the purpose of the book is included in the Introduction chapter demonstrating the retrieval system successfully retrieved the most relevant document to the input query, in this simple example.

In order to understand how the retrieval system works and how the “distance to the query vector” is computed, we need to understand how embeddings are created and how documents are indexed.

Embeddings

Embeddings are numerical representations of data (including text, images, audio, etc.) that capture meaning, allowing machines to process data quantitatively. Each embedding can be represented as a vector of floating-point numbers such that embedded data with similar meanings produce similar, i.e. close, vectors [1].

For text data, small distances among embeddings suggest high semantic relatedness and large distances suggest low semantic relatedness among the embedded texts. HuggingFace provides a leaderboard of embeddings models [HuggingFace, 2024i], which are ranked by dimensions such as classification, clustering and reranking performance.

Behind the scenes, ChromaDB is using the model all-MiniLM-L6-v2 by default [2] to create embeddings for the input documents and the query (see Fig. 5.7). This model is available in sentence_transformers [HuggingFace, 2024f]. Let’s see how it works.

Fig. 5.7 Embedding: From text to vectors.¶

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

embedding_model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

We replicate what ChromaDB did by embedding our chapters as well as input query using sentence transformers.

q = "What is the purpose of this book?"

docs_to_embed = [q] + chapters

embeddings = embedding_model.encode(docs_to_embed)

print(embeddings.shape)

(4, 384)

As a result, we obtain four 384-dimensional vectors representing our embeddings (one for each of the three chapters and one for the input query).

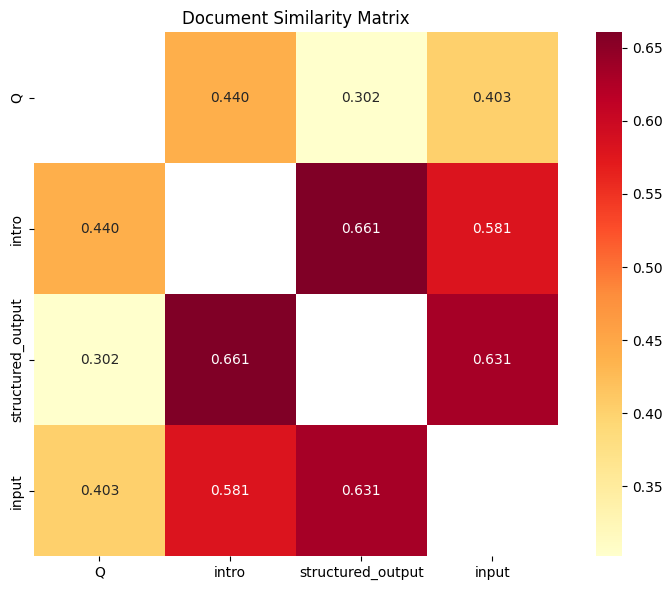

Now we can calculate similarity among the embeddings. By default, sentence transformers uses cosine similarity as similarity metric.

similarities = embedding_model.similarity(embeddings, embeddings)

similarities

tensor([[1.0000, 0.4402, 0.3022, 0.4028],

[0.4402, 1.0000, 0.6606, 0.5807],

[0.3022, 0.6606, 1.0000, 0.6313],

[0.4028, 0.5807, 0.6313, 1.0000]])

Let’s visualize the similarity matrix to better understand the relationships between our documents in Fig. 5.8. The top row of the matrix represents the similarity of the input query against all chapters. That’s exactly what we previously obtained by querying ChromaDB which returned a response with documents ranked by similarity to input query. As expected, the Introduction chapter is the most similar to the input query followed by the Input and Structured Output chapters, as we previously observed with ChromaDB.

Fig. 5.8 Similarity matrix heatmap showing relationships among query and chapters.¶

Calculating similarity among embeddings can become computationally intensive if brute force is used, i.e. pair-wise computation, as the number of documents grows in the knowledge base. Indexing is a technique to help address this challenge.

Indexing

Indexing is an optimization technique that makes similarity searches faster and more efficient.

Without indexing, finding similar vectors would require an exhaustive search - comparing a query vector against every single vector in the database. For large datasets, this becomes prohibitively slow.

Common indexing strategies include:

Tree-based Indexes

Examples include KD-trees and Ball trees

Work by partitioning the vector space into hierarchical regions

Effective for low-dimensional data but suffer from the “curse of dimensionality”

Graph-based Indexes

HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) is a prominent example

Creates a multi-layered graph structure for navigation

Offers excellent search speed but requires more memory

LSH (Locality-Sensitive Hashing)

Uses hash functions that map similar vectors to the same buckets

More memory-efficient than graph-based methods

May sacrifice some accuracy for performance

Quantization-based Indexes

Product Quantization compresses vectors by encoding them into discrete values

Reduces memory footprint significantly

Good balance between accuracy and resource usage

HNSW is the underlying library for ChromaDB vector indexing and search [ChromaDB, 2024a]. HNSW provides fast searches with high accuracy but uses more memory. LSH and quantization methods offer better memory efficiency but may sacrifice some precision.

But is the combination of indexing and basic embeddings-based similarity sufficient to retrieve relevant documents? Often not, as we will see next, as we cover reranking technique.

5.3.1.3. Reranking¶

Let’s go back to querying our vector database.

First, we write a query about how to get structured output from LLMs. Successfully retrieving the “Structured Output” chapter from the book as top result.

q = "How to get structured output from LLMs?"

res = query_collection(collection, q)

res.get("ids")

[['structured_output', 'input', 'intro']]

Next, we would like to obtain a tutorial on Docling, a tool we covered in this very chapter. However, we fail to obtain the correct chapter and instead obtain the “Introduction” chapter as a result.

q = "Docling tutorial"

res = query_collection(collection, q)

res.get("ids")

[['intro', 'input', 'structured_output']]

Retrieval systems solely based on vector similarity search might miss semantic relevance. That brings the need for techniques that can improve accuracy of the retrieval system. One such technique is re-ranking.

Re-ranking is a method that can improve accuracy of the retrieval system by re-ranking the retrieved documents based on their relevance to the input query.

In the following, we will use the sentence_transformers library to re-rank the retrieved documents based on their relevance to the input query. We utilize the CrossEncoder model to re-rank the documents. Cross-Encoder models are more accurate at judging relevance at the cost of speed compared to basic vector-based similarity.

We can implement a reranking step in a RAG system using a Cross-Encoder model in the following steps:

First, we initialize the Cross-Encoder model:

model = CrossEncoder('cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2', max_length=512)

Uses the

ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2model, which is specifically trained for passage rerankingSets a maximum sequence length of 512 tokens

This model is designed to score the relevance between query-document pairs

Then we perform the reranking:

scores = model.predict([(q, doc) for doc in res["documents"][0]])

Creates pairs of (query, document) for each retrieved document

The model predicts relevance scores for each pair

Higher scores indicate better semantic match between query and document

Finally, we select the best match:

print(res["documents"][0][np.argmax(scores)])

np.argmax(scores)finds the index of the highest scoring documentUses that index to retrieve the most relevant document

We obtain the following scores for the retrieved documents (“intro”, “input”, “structured_output”), the higher the score, the more relevant the document is in relation to the input query.

array([-8.52623 , -6.328738, -8.750055], dtype=float32)

As a result, we obtain the index of the highest scoring document, which corresponds to the “input” chapter. Hence, the re-ranking step successfully retrieved the correct chapter.

print(res["ids"][0][np.argmax(scores)])

input

In RAG systems, the idea is to first run semantic similarity on embeddings, which should be fast but potentially inaccurate, and then run reranking from the top-k results, which should be more accurate but slower. By doing so, we can balance the speed and accuracy of the retrieval system.

Hence, instead of going over all retrieved documents:

scores = model.predict([(q, doc) for doc in res["documents"][0]])

We would run reranking on the TOPK results, where TOPK <<< number of documents:

scores = model.predict([(q, doc) for doc in res["documents"][0][:TOPK]])

5.3.1.4. LLMs with RAG¶

We are finally ready to use the retrieval system to help the LLM answer our authorship question. A common way to integrate RAGs with LLMs is via in-context learning. With in-context learning the LLM learns from the retrieved documents by providing them in the context window as represented in Fig. 5.9. This is accomplished via a prompt template structure as follows.

Fig. 5.9 RAG LLM with In-Context Learning¶

rag_system_prompt_template = f"""

You are a helpful assistant that answers questions based on the provided CONTEXT.

CONTEXT: {context}

"""

user_prompt_template = f"""

QUESTION: {input}

"""

This prompt strategy demonstrates a common in-context learning pattern where retrieved documents are incorporated into the LLM’s context to enhance response accuracy and relevance. The prompt structure typically consists of a system prompt that:

Sets clear boundaries for the LLM to use information from the provided context

Includes the retrieved documents as context

This approach:

Reduces hallucination by grounding responses in source documents

Improves answer relevance by providing contextually relevant information to the LLM

The context variable is typically populated with the highest-scoring document(s) from the retrieval step, while the input variable contains the user’s original query.

def RAG_qa(client, model, context, input):

"""

Generate a summary of input using a given model

"""

rag_system_prompt_template = f"""You are a helpful assistant that answers questions based on the provided CONTEXT.

CONTEXT: {context}

"""

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "system", "content": rag_system_prompt_template},

{"role": "user", "content": f"QUESTION: {input}"}]

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

First, we set the LLM.

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import os

# Load environment variables from .env file

load_dotenv()

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

model = "gpt-4o-mini"

Then, we run the retrieval step.

res = query_collection(collection, q)

Next, we run the re-ranking step setting it to consider the TOPK retrieved documents.

TOPK = 2

scores = model.predict([(q, doc) for doc in res["documents"][0][:TOPK]])

res_reranked = res["documents"][0][np.argmax(scores)]

We then pass the top document as context and invoke the LLM with our RAG-based template leading to a successful response.

answer = RAG_qa(model, res_reranked[0], question)

answer

The author of the book "Taming LLMs" is Tharsis Souza.

In this section, we motivated the use of RAGs as a tool to equip LLMs with relevant context and provided a canonical implementation of its core components. RAGs, however, can be implemented in many shapes and forms and entire books have been written about them. We point the user to additional resources if more specialized techniques and architectures are needed [Alammar and Grootendorst, 2024, Diamant, 2024, Kimothi, 2024, AthinaAI, 2024].

Next, we discuss RAGs challenges and limitations and conclude our RAGs section envisioning the future of RAGs challenged by the rise of long-context language models.

5.3.2. Challenges and Limitations¶

While RAG systems offer powerful capabilities for enhancing LLM responses with external knowledge, they face several significant challenges and limitations that require careful consideration:

Data Quality and Accuracy: The effectiveness of RAG systems fundamentally depends on the quality and reliability of their knowledge sources. When these sources contain inaccurate, outdated, biased, or incomplete information, the system’s responses become unreliable. This challenge is particularly acute when dealing with rapidly evolving topics or when sourcing information from unverified channels.

Computational Cost and Latency: Implementing RAG systems at scale presents computational and operational challenges. The process of embedding documents, maintaining vector databases, and performing similarity searches across large knowledge bases demands computational, and operational resources. In real-time applications, these requirements can introduce noticeable latency, potentially degrading the user experience and limiting practical applications.

Explainability and Evaluation: The complexity of RAG systems, arising from the intricate interaction between retrieval mechanisms and generative models, makes it difficult to trace and explain their reasoning processes. Traditional evaluation metrics often fail to capture the nuanced aspects of RAG performance, such as contextual relevance and factual consistency. This limitation hampers both system improvement and stakeholder trust. Readers are encouraged to read Chapter The Evals Gap for general LLM evaluation issues as well as consider tools such as Ragas [Ragas, 2024] for RAG evaluation.

Hallucination Management: Though RAG systems help ground LLM responses in source documents, they do not completely eliminate hallucinations. The generative component may still produce content that extrapolates beyond or misinterprets the retrieved context. This risk becomes particularly concerning when the system confidently presents incorrect information with apparent source attribution.

Moreover, recent research has shed light on critical limitations of key techniques used in RAGs systems. A relevant finding pertains to reranking, which has shown [Jacob et al., 2024]:

Diminishing Returns: Performance degrades as the number of documents (K) increases, sometimes performing worse than basic retrievers when dealing with large datasets.

Poor Document Discrimination: Rerankers can be misled by irrelevant documents, sometimes assigning high scores to content with minimal relevance to the query.

Consistency Issues: Performance and relative rankings between different rerankers can vary significantly depending on the number of documents being processed.

5.3.3. Will RAGs exist in the future?¶

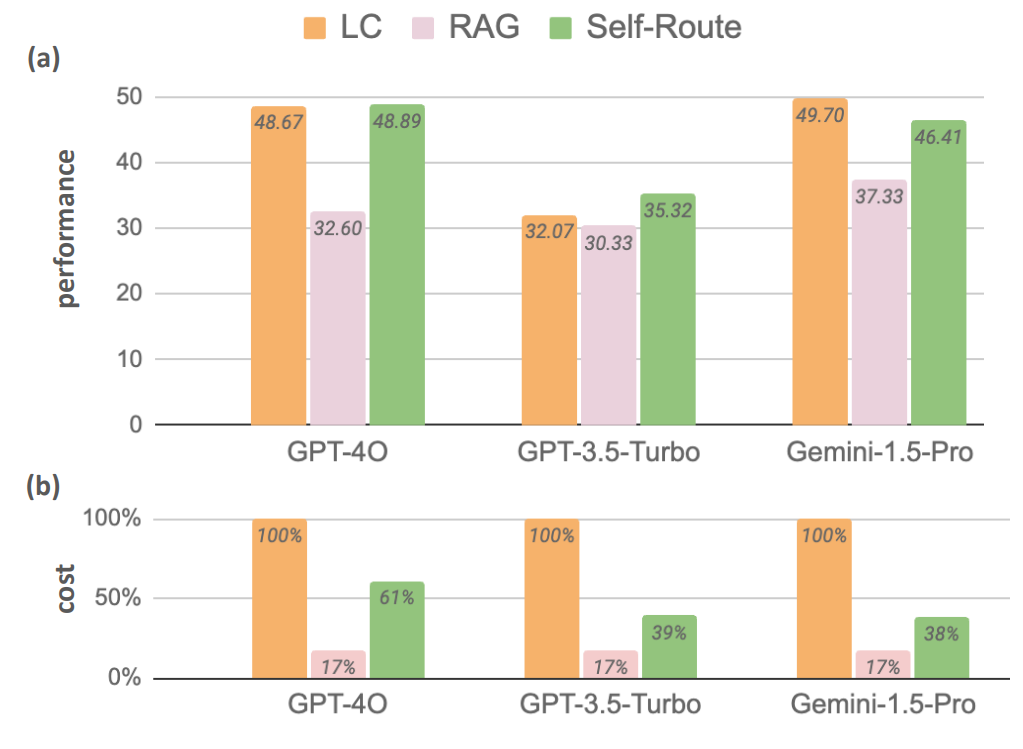

This question is posed as we contrast RAGs with LLMs with long-context windows (LCs).

Recent research has shed light on this specific point [Li et al., 2024] suggesting a trade-off between cost and performance. On the one hand, RAGs can be seen as a cost-effective alternative to LC models:

RAGs offer lower computational cost compared to LCs due to the significantly shorter input length required for processing.

This cost-efficiency arises because RAG reduces the number of input tokens to LLMs, which in turn reduces overall usage cost.

On the other hand, this RAG benefit is achieved at the cost of performance:

Recent advancements in LLMs, in particular with Gemini-1.5 and GPT-4o models, demonstrate capabilities in understanding long contexts directly, which enables them to outperform RAG in terms of average performance.

LC models can process extremely long contexts, such as Gemini 1.5 which can handle up to 1 million tokens, and these models benefit from large-scale pretraining to develop strong long-context capabilities.

This cost-performance trade-off is illustrated in Fig. 5.10, where LC models outperform RAGs in terms of average performance while RAGs are more cost-effective.

Fig. 5.10 Long-Context LLMs demonstrate superior performance while RAGs are more cost-effective [Li et al., 2024].¶

Fig. 5.10 also shows a model called “SELF-ROUTE” which combines RAG and LC by routing queries based on model self-reflection. This is a hybrid approach that reduces computational costs while maintaining performance comparable to LC. The advantage of SELF-ROUTE is most significant for smaller values of k, where k is the number of retrieved text chunks, and SELF-ROUTE shows a marked improvement in performance over RAG, while as k increases the performance of RAG and SELF-ROUTE approaches that of LC.

Another example of a hybrid approach that combines the benefits of both LC and RAGs is RetroLLM [Li et al., 2024], which is a unified framework that integrates retrieval and generation into a single process, enabling language models to generate fine-grained evidence directly from a corpus. The key contribution is that this approach delivers those benefits while eliminating the need for a separate retriever, addressing limitations of traditional RAG methods. Experimental results demonstrate RetroLLM’s superior performance compared to traditional RAG methods, across both in-domain and out-of-domain tasks. It also achieves a significant reduction in token consumption due to its fine-grained evidence retrieval.

CAG [Chan et al., 2024] is another solution that eliminates the need for RAGs as it proposes cache-augmented generation (CAG). CAG preloads all relevant data into a large language model’s extended context window, eliminating the need for real-time retrieval and improving speed and accuracy. This is achieved by precomputing a key-value cache, further optimizing inference time. CAG demonstrates superior performance compared to RAG by achieving higher BERT scores in most evaluated scenarios, indicating better answer quality, and by having significantly reduced generation times. These results suggest that CAG can be both more accurate and more efficient than traditional RAG systems.

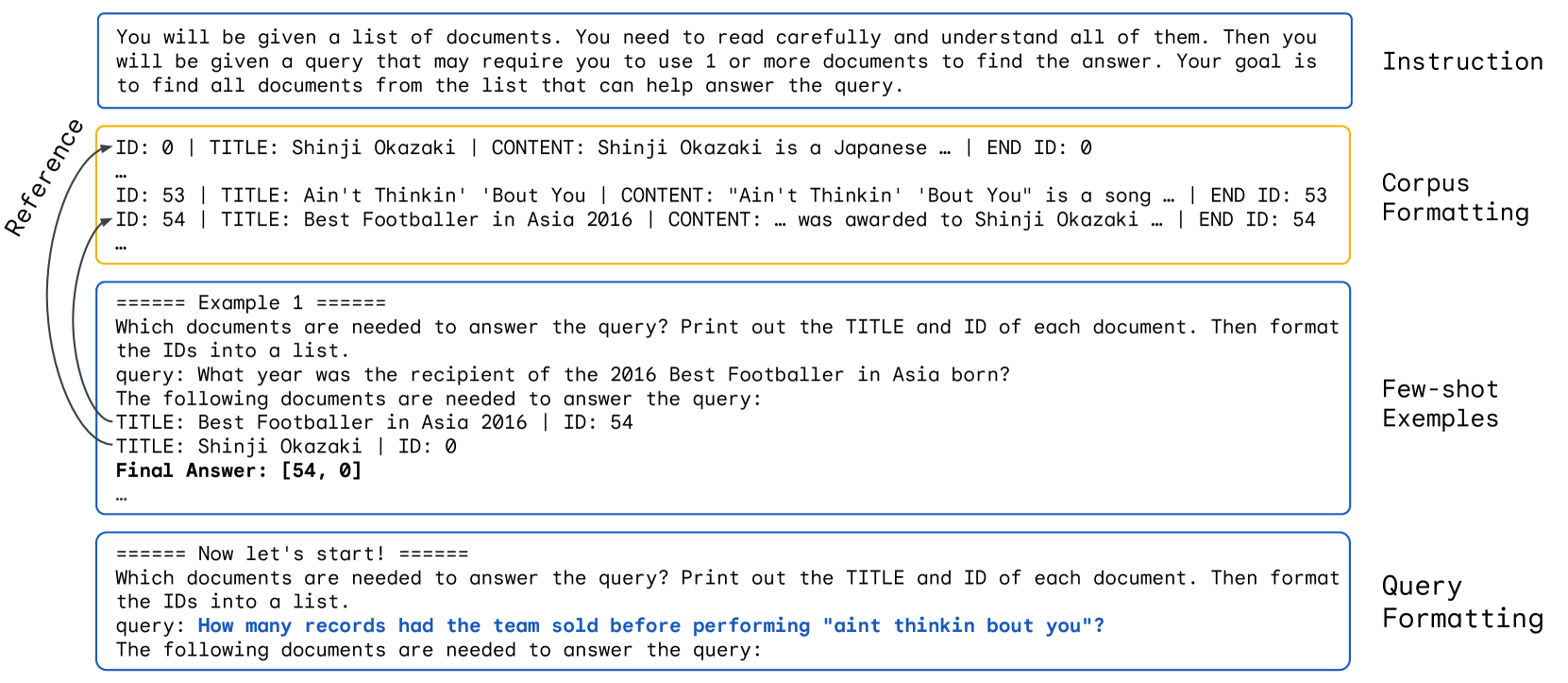

Another relevant development in this area is the introduction of LOFT [Lee et al., 2024], a benchmark to assess this paradigm shift from RAGs to LCs, using real-world tasks requiring context up to millions of tokens. Evidence suggests LCs can deliver performance with simplified pipelines compared to RAGs, particularly for tasking requiring multi-hop reasoning over long contexts when using Chain-of-Thought [Wei et al., 2023]. However, LCs can still be outperformed by specialized retrievers, in particular Gecko, a specialized model fine-tuned on extensive text retrieval and similarity tasks.

Bottom-line: Do we really need RAGs? The answer is conditional:

RAG may be relevant when cost-effectiveness is a key requirement and where the model needs to access vast amounts of external knowledge without incurring high computational expenses. However, as LLMs context window sizes increase and LLMs cost per input token decreases, RAGs may not be as relevant as it was before.

Long-context LLMs are superior when performance is the primary concern, and the model needs to handle extensive texts that require deep contextual understanding and reasoning.

Hybrid approaches like SELF-ROUTE are valuable as they combine the strengths of RAG and LC offering a practical balance between cost and performance, especially for applications where both factors are critical.

Ultimately, the choice among RAG, LC, or a hybrid method depends on the specific requirements of the task, available resources, and the acceptable trade-off between cost and performance.

In a later case study, we demonstrate the power of LCs as we construct a Quiz generator with citations over a large knowledge base without the use of chunking nor RAGs.

5.4. A Note on Frameworks¶

We have covered a few open source tools for parsing data and provided a canonical RAG pipeline directly using an open source VectorDB together with an LLM. There is a growing number of frameworks that offer similar functionality wrapping the same core concepts at a higher level of abstraction. The two most popular ones are Langchain and LlamaIndex.

For instance, the code below shows how to use LlamaIndex’s LlamaParse for parsing input documents, which offers support for a wide range of file formats (e.g. .pdf, .pptx, .docx, .xlsx, .html). We observe that the code is very similar to the one we used for MarkitDown and Docling.

from llama_parse import LlamaParse

# Initialize the parser

parser = LlamaParse(

api_key="llx-your-api-key-here",

result_type="markdown", # Can be "markdown" or "text"

verbose=True

)

documents = parser.load_data(["./doc1.pdf", "./doc2.pdf"])

As another example, the code below replicates our ChromaDB-based retrieval system using LlamaIndex [LlamaIndex, 2024].

As we can see, similar concepts are used:

Documents to represent elements of the knowledge base

Collections to store the documents

Indexing of embeddings in the VectorDB and finally

Querying the VectorDB to retrieve the documents

import chromadb

from llama_index.core import VectorStoreIndex, SimpleDirectoryReader

from llama_index.vector_stores.chroma import ChromaVectorStore

from llama_index.core import StorageContext

# load some documents

documents = SimpleDirectoryReader("./data").load_data()

# initialize client, setting path to save data

db = chromadb.PersistentClient(path="./chroma_db")

# create collection

chroma_collection = db.get_or_create_collection("tamingllms")

# assign chroma as the vector_store to the context

vector_store = ChromaVectorStore(chroma_collection=chroma_collection)

storage_context = StorageContext.from_defaults(vector_store=vector_store)

# create your index

index = VectorStoreIndex.from_documents(

documents, storage_context=storage_context

)

# create a query engine and query

query_engine = index.as_query_engine()

response = query_engine.query("Who is the author of Taming LLMs?")

print(response)

Frameworks are useful for quickly prototyping RAG systems and for building applications on top of them as they provide a higher level of abstraction and integration with third-party libraries. However, the underlying concepts are the same as the ones we have covered in this chapter. More often than not, problems arise when developers either do not understand the underlying concepts or fail to understand the details of the implement behind the abstractions provided by the framework. Therefore, it is recommended to try and start your implementation using lower level tools as much as possible and only when (i) the underlying problem as well as (ii) the desired solution are well understood, then consider moving to higher level frameworks if really needed.

5.5. Case Studies¶

This section presents two case studies to complement topics we have covered in this chapter in the context of managing input data for LLMs.

First, we cover content chunking, in particular Content Chunking with Contextual Linking which showcases how intelligent chunking strategies can overcome both context window and output token limitations. This case study illustrates techniques for breaking down and reassembling content while maintaining coherence, enabling the generation of high-quality long-form outputs despite model constraints.

Second, we build a Quiz generator with citations using long context window. Not all knowledge intense applications require RAGs. In this case study, we show how to use long context window as well as some additional input management techniques such as prompt caching for efficiency and reference management to enhance response accuracy and verifiability. These approaches show how to maximize the benefits of larger context models while maintaining response quality.

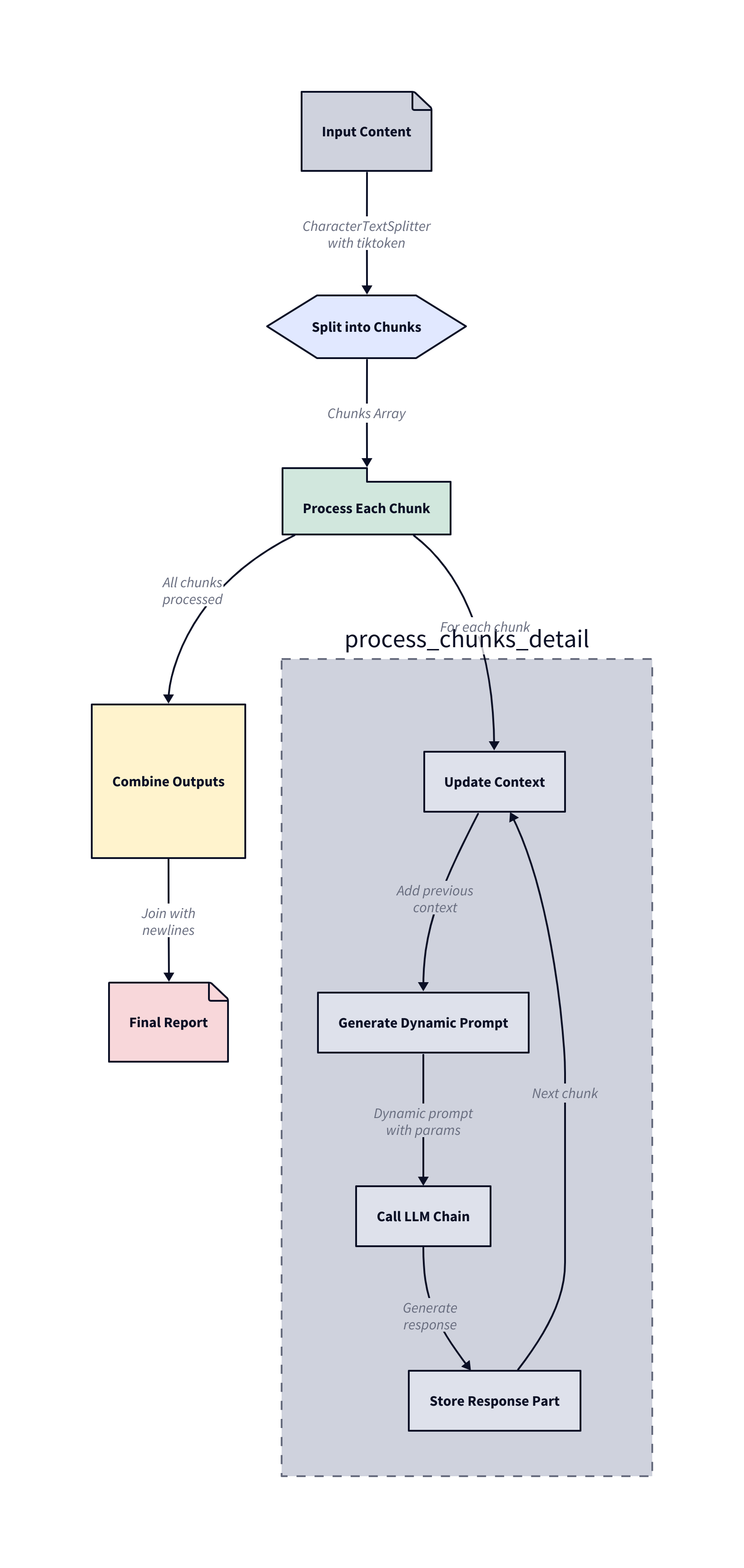

5.5.1. Case Study I: Content Chunking with Contextual Linking¶

Content chunking is commonly used to breakdown long-form content into smaller, manageable chunks. In the context of RAGs, this can be helpful not only to help the retrieval system find more contextually relevant documents but also lead to a more cost efficient LLM solution since fewer tokens are processed in the context window. Furthermore, semantic chunking can increase accuracy of RAG systems [ZenML, 2024].

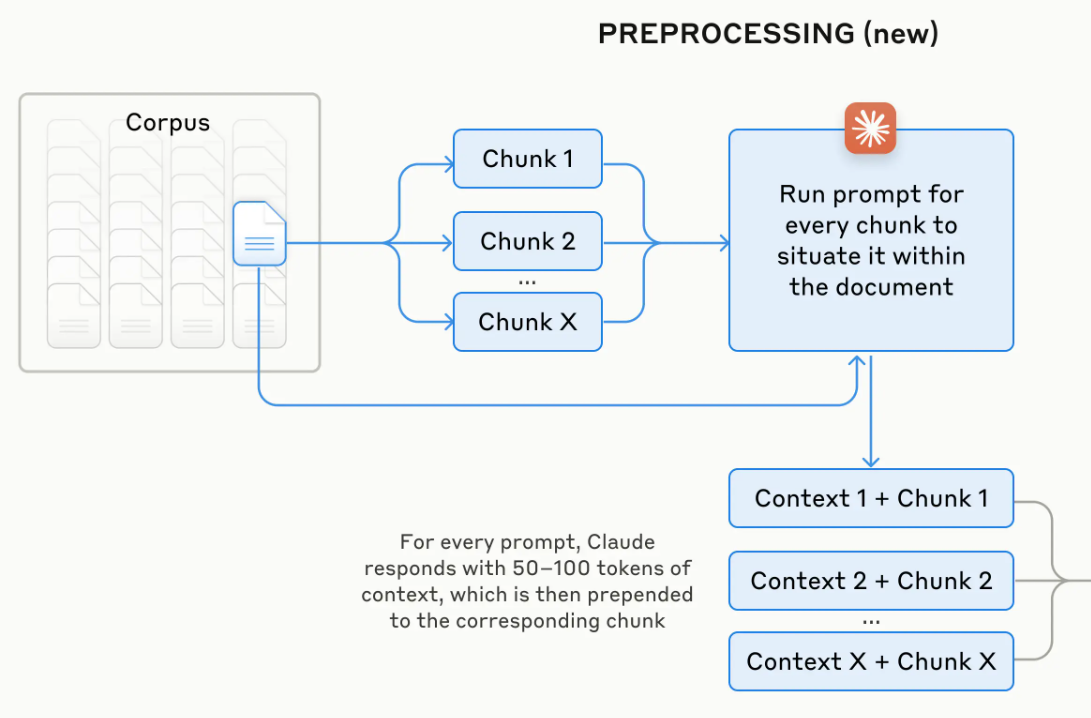

Content chunking with contextual linking is a chunking technique that seeks to split input content while keeping chunk-specific context, hence allowing the LLM to maintain coherence and context when generating responses per chunks. In that way, this technique tackles two key problems:

The LLM’s inability to process long inputs to do context-size limits

The LLM’s inability to maintain coherence and context when generating responses per chunks

As a consequence, a third problem is also tackled: LLM’s inability to generate long-form content due to the max_output_tokens limitation. Since we generate responses per chunk, as we will see later, we end up with a solution that is capable of generating long-form content while maintaining coherence.

We exemplify this technique by following these steps:

Chunking the Content: The input content is split into smaller chunks. This allows the LLM to process each chunk individually, focusing on generating a complete and detailed response for that specific section of the input.

Maintaining Context: Each chunk is linked with contextual information from the previous chunks. This helps in maintaining the flow and coherence of the content across multiple chunks.

Generating Linked Prompts: For each chunk, a prompt is generated that includes the chunk’s content and its context. This prompt is then used to generate the output for that chunk.

Combining the Outputs: The outputs of all chunks are combined to form the final long-form content.

Let’s examine an example implementation of this technique.

5.5.1.1. Generating long-form content¶

Goal: Generate a long-form report analyzing a company’s financial statement.

Input: A company’s 10K SEC filing.

Fig. 5.11 Content Chunking with Contextual Linking Schematic Representation.¶

The diagram in Fig. 5.11 illustrates the process we will follow for handling long-form content generation with Large Language Models through “Content Chunking with Contextual Linking.” It shows how input content is first split into manageable chunks using a chunking function (e.g. CharacterTextSplitter with tiktoken tokenizer), then each chunk is processed sequentially while maintaining context from previous chunks. For each chunk, the system updates the context, generates a dynamic prompt with specific parameters, makes a call to the LLM chain, and stores the response. After all chunks are processed, the individual responses are combined with newlines to create the final report, effectively working around the token limit constraints of LLMs while maintaining coherence across the generated content.

Step 1: Chunking the Content

There are different methods for chunking, and each of them might be appropriate for different situations. However, we can broadly group chunking strategies in two types:

Fixed-size Chunking: This is the most common and straightforward approach to chunking. We simply decide the number of tokens in our chunk and, optionally, whether there should be any overlap between them. In general, we will want to keep some overlap between chunks to make sure that the semantic context doesn’t get lost between chunks. Fixed-sized chunking may be a reasonable path in many common cases. Compared to other forms of chunking, fixed-sized chunking is computationally cheap and simple to use since it doesn’t require the use of any specialied techniques or libraries.

Content-aware Chunking: These are a set of methods for taking advantage of the nature of the content we’re chunking and applying more sophisticated chunking to it. Examples include:

Sentence Splitting: Many models are optimized for embedding sentence-level content. Naturally, we would use sentence chunking, and there are several approaches and tools available to do this, including naive splitting (e.g. splitting on periods), NLTK, and spaCy.

Recursive Chunking: Recursive chunking divides the input text into smaller chunks in a hierarchical and iterative manner using a set of separators.

Semantic Chunking: This is a class of methods that leverages embeddings to extract the semantic meaning present in your data, creating chunks that are made up of sentences that talk about the same theme or topic.

Here, we will utilize

langchainfor a content-aware sentence-splitting strategy for chunking. Langchain offers several text splitters [LangChain, 2024] such as JSON-, Markdown- and HTML-based or split by token. We will use theCharacterTextSplitterwithtiktokenas our tokenizer to count the number of tokens per chunk which we can use to ensure that we do not surpass the input token limit of our model.

def get_chunks(text: str, chunk_size: int, chunk_overlap: int) -> list:

"""

Split input text into chunks of specified size with specified overlap.

Args:

text (str): The input text to be chunked.

chunk_size (int): The maximum size of each chunk in tokens.

chunk_overlap (int): The number of tokens to overlap between chunks.

Returns:

list: A list of text chunks.

"""

from langchain_text_splitters import CharacterTextSplitter

text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter.from_tiktoken_encoder(chunk_size=chunk_size, chunk_overlap=chunk_overlap)

return text_splitter.split_text(text)

Step 2: Writing the Base Prompt Template

We will write a base prompt template which will serve as a foundational structure for all chunks, ensuring consistency in the instructions and context provided to the language model. The template includes the following parameters:

role: Defines the role or persona the model should assume.context: Provides the background information or context for the task.instruction: Specifies the task or action the model needs to perform.input_text: Contains the actual text input that the model will process.requirements: Lists any specific requirements or constraints for the output.

from langchain_core.prompts import PromptTemplate

def get_base_prompt_template() -> str:

base_prompt = """

ROLE: {role}

CONTEXT: {context}

INSTRUCTION: {instruction}

INPUT: {input}

REQUIREMENTS: {requirements}

"""

prompt = PromptTemplate.from_template(base_prompt)

return prompt

We will write a simple function that returns an LLMChain which is a simple langchain construct that allows you to chain together a combination of prompt templates, language models and output parsers.

from langchain_core.output_parsers import StrOutputParser

from langchain_community.chat_models import ChatLiteLLM

def get_llm_chain(prompt_template: str, model_name: str, temperature: float = 0):

"""

Returns an LLMChain instance using langchain.

Args:

prompt_template (str): The prompt template to use.

model_name (str): The name of the model to use.

temperature (float): The temperature setting for the model.

Returns:

llm_chain: An instance of the LLMChain.

"""

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import os

# Load environment variables from .env file

load_dotenv()

api_key_label = model_name.split("/")[0].upper() + "_API_KEY"

llm = ChatLiteLLM(

model=model_name,

temperature=temperature,

api_key=os.environ[api_key_label],

)

llm_chain = prompt_template | llm | StrOutputParser()

return llm_chain

Step 3: Constructing Dynamic Prompt Parameters

Now, we will write a function (get_dynamic_prompt_template) that constructs prompt parameters dynamically for each chunk.

from typing import Dict

def get_dynamic_prompt_params(prompt_params: Dict,

part_idx: int,

total_parts: int,

chat_context: str,

chunk: str) -> str:

"""

Construct prompt template dynamically per chunk while maintaining the chat context of the response generation.

Args:

prompt_params (Dict): Original prompt parameters

part_idx (int): Index of current conversation part

total_parts (int): Total number of conversation parts

chat_context (str): Chat context from previous parts

chunk (str): Current chunk of text to be processed

Returns:

str: Dynamically constructed prompt template with part-specific params

"""

dynamic_prompt_params = prompt_params.copy()

# saves the chat context from previous parts

dynamic_prompt_params["context"] = chat_context

# saves the current chunk of text to be processed as input

dynamic_prompt_params["input"] = chunk

# Add part-specific instructions

if part_idx == 0: # Introduction part

dynamic_prompt_params["instruction"] = f"""

You are generating the Introduction part of a long report.

Don't cover any topics yet, just define the scope of the report.

"""

elif part_idx == total_parts - 1: # Conclusion part

dynamic_prompt_params["instruction"] = f"""

You are generating the last part of a long report.

For this part, first discuss the below INPUT. Second, write a "Conclusion" section summarizing the main points discussed given in CONTEXT.

"""

else: # Main analysis part

dynamic_prompt_params["instruction"] = f"""

You are generating part {part_idx+1} of {total_parts} parts of a long report.

For this part, analyze the below INPUT.

Organize your response in a way that is easy to read and understand either by creating new or merging with previously created structured sections given in CONTEXT.

"""

return dynamic_prompt_params

Step 4: Generating the Report

Finally, we will write a function that generates the actual report by calling the LLMChain with the dynamically updated prompt parameters for each chunk and concatenating the results at the end.

def generate_report(input_content: str, llm_model_name: str,

role: str, requirements: str,

chunk_size: int, chunk_overlap: int) -> str:

# stores the parts of the report, each generated by an individual LLM call

report_parts = []

# split the input content into chunks

chunks = get_chunks(input_content, chunk_size, chunk_overlap)

# initialize the chat context with the input content

chat_context = input_content

# number of parts to be generated

num_parts = len(chunks)

prompt_params = {

"role": role, # user-provided

"context": "", # dinamically updated per part

"instruction": "", # dynamically updated per part

"input": "", # dynamically updated per part

"requirements": requirements #user-priovided

}

# get the LLMChain with the base prompt template

llm_chain = get_llm_chain(get_base_prompt_template(),

llm_model_name)

# dynamically update prompt_params per part

print(f"Generating {num_parts} report parts")

for i, chunk in enumerate(chunks):

dynamic_prompt_params = get_dynamic_prompt_params(

prompt_params,

part_idx=i,

total_parts=num_parts,

chat_context=chat_context,

chunk=chunk

)

# invoke the LLMChain with the dynamically updated prompt parameters

response = llm_chain.invoke(dynamic_prompt_params)

# update the chat context with the cummulative response

if i == 0:

chat_context = response

else:

chat_context = chat_context + response

print(f"Generated part {i+1}/{num_parts}.")

report_parts.append(response)

report = "\n".join(report_parts)

return report

Example Usage

# Load the text from sample 10K SEC filing

with open('../data/apple.txt', 'r') as file:

text = file.read()

# Define the chunk and chunk overlap size

MAX_CHUNK_SIZE = 10000

MAX_CHUNK_OVERLAP = 0

report = generate_report(text, llm_model_name="gemini/gemini-1.5-flash-latest",

role="Financial Analyst",

requirements="The report should be in a readable, structured format, easy to understand and follow. Focus on finding risk factors and market moving insights.",

chunk_size=MAX_CHUNK_SIZE,

chunk_overlap=MAX_CHUNK_OVERLAP)

# Save the generated report to a local file

with open('data/apple_report.txt', 'w') as file:

file.write(report)

# Read and display the generated report

with open('../data/apple_report.txt', 'r') as file:

report_content = file.read()

from IPython.display import Markdown

# Display first and last 10% of the report content

report_lines = report_content.splitlines()

total_lines = len(report_lines)

quarter_lines = total_lines // 10

top_portion = '\n'.join(report_lines[:quarter_lines])

bottom_portion = '\n'.join(report_lines[-quarter_lines:])

display(Markdown(f"{top_portion}\n\n (...) \n\n {bottom_portion}"))

Introduction

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Apple Inc.’s financial performance and position for the fiscal year ended September 28, 2024, as disclosed in its Form 10-K filing with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission. The analysis will focus on identifying key risk factors impacting Apple’s business, evaluating its financial health, and uncovering market-moving insights derived from the provided data. The report will delve into Apple’s various segments, product lines, and services, examining their performance and contributions to overall financial results. Specific attention will be paid to identifying trends, potential challenges, and opportunities for future growth. The analysis will also consider the broader macroeconomic environment and its influence on Apple’s operations and financial outlook. Finally, the report will incorporate relevant information from Apple’s definitive proxy statement for its 2025 annual meeting of shareholders, as incorporated by reference in the Form 10-K.

PART 2: Key Risk Factors and Market-Moving Insights

This section analyzes key risk factors disclosed in Apple Inc.’s 2024 Form 10-K, focusing on their potential impact on financial performance and identifying potential market-moving insights. The analysis is structured around the major risk categories identified in the filing.

2.1 Dependence on Third-Party Developers:

Apple’s success is heavily reliant on the continued support and innovation of third-party software developers. The Form 10-K highlights several critical aspects of this dependence:

Market Share Vulnerability: Apple’s relatively smaller market share in smartphones, personal computers, and tablets compared to competitors (Android, Windows, gaming consoles) could discourage developers from prioritizing Apple’s platform, leading to fewer high-quality apps and potentially impacting customer purchasing decisions. This is a significant risk, especially given the rapid pace of technological change. A decline in app availability or quality could negatively impact sales and market share. Market-moving insight: Monitoring developer activity and app quality across competing platforms is crucial for assessing this risk. Any significant shift in developer focus away from iOS could be a negative market signal.

App Store Dynamics: While Apple allows developers to retain most App Store revenue, its commission structure and recent changes (e.g., complying with the Digital Markets Act (DMA) in the EU) introduce uncertainty. Changes to the App Store’s policies or fee structures could materially affect Apple’s revenue and profitability. Market-moving insight: Closely monitoring regulatory developments (especially concerning the DMA) and their impact on App Store revenue is essential. Any significant changes to Apple’s App Store policies or revenue streams could trigger market reactions.

Content Acquisition and Creation: Apple’s reliance on third-party digital content providers for its services introduces risks related to licensing agreements, competition, and pricing. The cost of producing its own digital content is also increasing due to competition for talent and subscribers. Failure to secure or create appealing content could negatively impact user engagement and revenue. Market-moving insight: Analyzing the success of Apple’s original content initiatives and the renewal rates of third-party content agreements will provide insights into this risk.

2.2 Operational Risks:

(…)

The reconciliation of segment operating income to consolidated operating income reveals that research and development (R&D) and other corporate expenses significantly impact overall profitability. While increased R&D is generally positive, it reduces short-term profits. The geographical breakdown of net sales and long-lived assets further emphasizes the concentration of Apple’s business in the U.S. and China. Market-moving insight: Continued weakness in the Greater China market, sustained flat iPhone sales, or any significant changes in R&D spending should be closely monitored for their potential impact on Apple’s financial performance and investor sentiment.

5.4 Auditor’s Report and Internal Controls:

The auditor’s report expresses an unqualified opinion on Apple’s financial statements and internal control over financial reporting. However, it identifies uncertain tax positions as a critical audit matter. The significant amount of unrecognized tax benefits ($22.0 billion) and the complexity involved in evaluating these positions highlight a substantial risk. Management’s assessment of these positions involves significant judgment and relies on interpretations of complex tax laws. Apple’s management also asserts that its disclosure controls and procedures are effective. Market-moving insight: Any changes in tax laws, unfavorable rulings on uncertain tax positions, or weaknesses in internal controls could materially affect Apple’s financial results and investor confidence.

Conclusion

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Apple Inc.’s financial performance and position for fiscal year 2024. While Apple maintains a strong financial position with substantial cash reserves and a robust capital return program, several key risk factors could significantly impact its future performance. These risks include:

Dependence on third-party developers: A shift in developer focus away from iOS or changes to the App Store’s policies could negatively impact Apple’s revenue and profitability.

Operational risks: Employee retention challenges, reseller dependence, and cybersecurity threats pose significant operational risks.

Legal and regulatory risks: Ongoing antitrust litigation, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) compliance, and data privacy regulations introduce substantial legal and regulatory uncertainties.

Financial risks: Volatility in sales and profit margins, foreign exchange rate fluctuations, credit risk, and tax risks could impact Apple’s financial performance.

Supply chain concentration: Apple’s reliance on a concentrated network of outsourcing partners, primarily located in a few Asian countries, and dependence on single or limited sources for certain custom components, exposes the company to significant supply chain risks.

Uncertain tax positions: The significant amount of unrecognized tax benefits represents a substantial uncertainty that could materially affect Apple’s financial results.